Privacy Risks of Chinese EVs

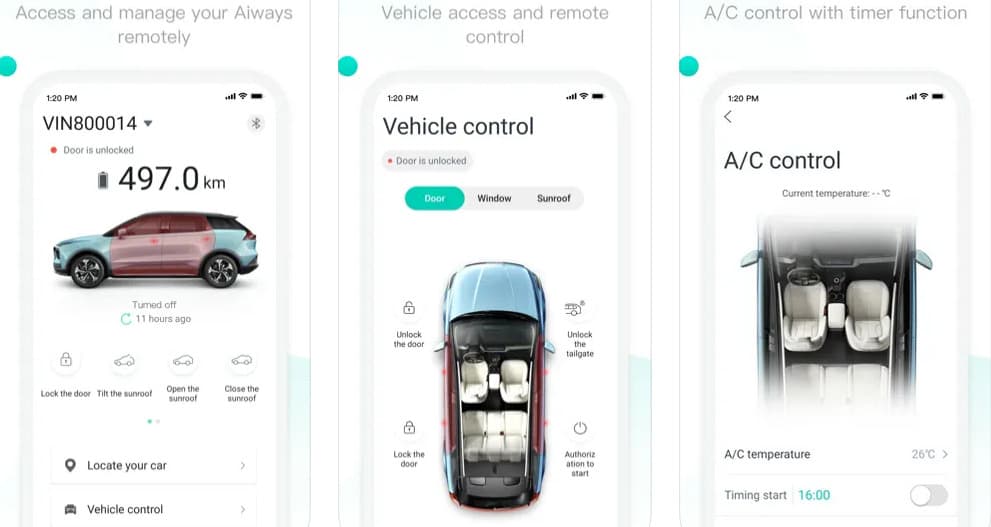

As sales of Chinese EVs rapidly increase around the world, we investigated the privacy implications of owning these high-tech internet-connected vehicles that require a mobile app to unlock all their features.

Our goal is to raise awareness about the personal data harvested by these ever more popular EVs and their associated mobile apps. We hope that highlighting the risks posed to consumer privacy by the growth of this internet-connected technology will lead to an improvement in data privacy protections for everyone.

Smart car data is extremely sensitive. It can be used to track individuals’ movements, which not only reveals where they live and work but also their hobbies, personal relationships, health and finances. This information is valuable not only for governments but also businesses such as insurance companies, whose actions can have a significant impact on our everyday lives.

Exports of Chinese EVs have surged by 851% over the last three years, with many of those vehicles heading to Europe.[1] In 2023 alone, shipments to the European Union increased by 112% compared to 2022 and by 361% versus 2021.[2]

While it’s clear that the appeal of these new EVs, which are typically priced 20% lower than competing brands’ vehicles, causes a headache for the automotive old guard, it could also represent a privacy timebomb for consumers.

There are also question marks over the closeness of the relationship between the EV industry and the government in China.

Smart cars in general already have a poor reputation for privacy even without adding in the spectre of mass data harvesting by the Chinese state.[3]

The Chinese government pumped $57 billion in subsidies into its EV industry between 2016 and 2022. It remains unknown whether this generous funding came with any conditions relating to the goldmine of data generated by smart cars. However, it doesn’t seem unreasonable to suggest that any company that accepts substantial state handouts in an industry as competitive as the manufacture of EVs will be beholden to some degree to their benefactors.

Moreover, four leading EV exporters have clear ties to the state: MG parent company SAIC is wholly state-owned while Nio, HiPhi and Xpeng have all received significant government investment. The billionaire owner of Geely (the parent company of Zeekr, Volvo, and Polestar) is politically active and appears close to the government.[4]

As the Chinese share of the European EV market has already grown to 8% this year and is set to reach 15% by 2025,[5] the time felt ripe to investigate the privacy practices of the leading exporters.

We did a deep dive into the personal data collection, sharing, storage and transfer practices by these companies (jump straight to our GDPR compliance section for a quick overview of this). We also analyzed the accuracy of the app store labels for their mobile apps, along with identifying Android app permissions and any third-party software libraries that posed a privacy risk to users.

The ten companies we investigated were:

- Aiways

- BYD

- GWM (Great Wall Motors)

- HiPhi

- MG (SAIC)

- Nio

- Polestar (Geely)

- Volvo (Geely)

- Xpeng

- Zeekr (Geely)

Which brands pose the most risk to data privacy?

The EV brand with the highest data privacy risk was Polestar, which was primarily due to the lack of an appropriate privacy policy. However HiPhi and Aiways also performed poorly overall.

The best-performing companies on data privacy were MG and Volvo.

The following table summarises the overall performance of each manufacturer across each of the privacy categories that formed our analysis.

The companies are ordered from worst to best-performing in terms of data privacy.

* Aiways and GWM don’t claim to collect as much data as their rivals however there are significant gaps in their policies in this area.

** Volvo’s privacy labels were inaccurate for iOS app but accurate for the Android version.