VPN Censorship: Which Countries Block VPN Websites?

Analysis of over 12 million internet measurement tests reveals the countries that block access to VPN and other privacy enhancing technologies the most.

Country Analysis

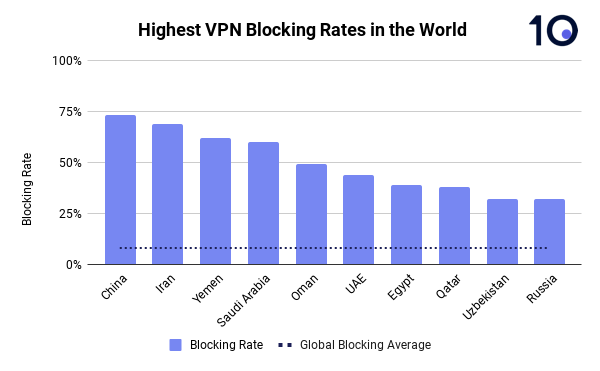

- China blocks access to VPN and other censorship circumvention websites 73% of the time, more than any other country

- The global average blocking rate for such sites is just 8%

- China is followed by Iran (69%), Yemen (62%), Saudi Arabia (60%), Oman (49%), United Arab Emirates (44%), Egypt (39%), Qatar (38%), Russia (32%) and Uzbekistan (32%)

- 7 of the 10 countries that block access to VPN websites most consistently are in MENA

- The UK and US each block access 4% of the time

Website Analysis

- Tor Project, NordVPN, SecureVPN, SurfShark and Psiphon are among the most consistently blocked websites in the top ten countries

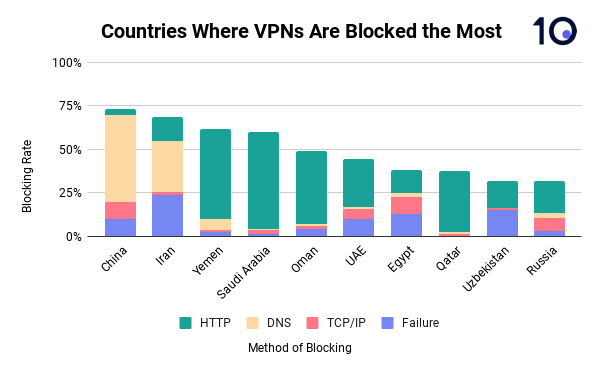

- DNS and HTTP/HTTPs interference are the most common ways the websites are blocked, with significantly lower rates of IP blocking

VPN Blocking

Virtual Private Networks (VPN) and other privacy-enhancing technologies are vital for people living in countries where the internet is heavily restricted. They help people bypass content blocks and stay secure in highly monitored environments.

Unsurprisingly then, these tools have also come under attack from governments looking to control their populations online.

Governments disrupt access to VPN apps in a variety of ways. They can force app stores to remove the programs, interfere with the protocols that enable them to work, and pass legislation that criminalizes their use.

One of the most common ways governments prevent people from using VPNs is by blocking access to their websites. Doing so prevents people from downloading the apps directly from the developers and can interfere with peoples’ ability to log in and use the programs by disrupting interactions with the software’s backend, which may be hosted on related subdomains.

To determine which countries block access to VPN and other privacy-enhancing technologies the most, we analyzed over 13 million internet measurement tests from more than 100 countries collected by the Open Observatory for Network Interference (OONI) over the past six months. The data reveals the reachability of websites and provides vital insights into how content restrictions are imposed.

Websites tested range from some of the most well-known VPN brands, including Hola and TunnelBear, to more obscure anonymization and privacy-enhancing technologies.

As internet censorship is not static, measuring blocks repeatedly across various geographies and networks, helps establish a more accurate overview of a country’s information controls.

The extent to which VPN and other privacy-enhancing technologies are restricted also serves as a useful proxy for understanding the state of internet freedom in a given country and may serve as an important indicator for other digital rights violations.

Which Countries Block VPN Websites the Most?

Unsurprisingly, China blocked access to VPN and other circumvention tools more consistently than any other. In total, 73% of attempts to access VPN websites failed. That’s more than eight times (812%) more than the global average, which stands at just 8%.

While China’s draconian approach to internet regulation is well known, our research shows that even they are unable to block all websites, on all of the networks, all of the time. In fact, around one in four attempts were successful.

Despite that, censorship of VPNs in mainland China remains the highest in the world and the website blocks are frequently combined with technical disruptions to VPN protocols and the criminalization of their use.

In contrast, while the censorship in Hong Kong has become increasingly widespread in recent years, just 4% of attempts to access VPN and other censorship circumvention tools were blocked. That’s the same as in the UK and US.

Chart showing the countries that block access to VPN websites the most frequently

All of the countries listed above have long histories of restricting access to information and curtailing freedom of expression both online and offline.

7 of the 10 countries that block access to VPN and other circumvention technologies are located in MENA. This speaks to the restrictive information controls that exist and mirrors the increasing criminalization of their use across the region.

However, not every country in the region is implementing restrictions. In Tunisia, just 1% of more than 30,000 attempted connections were blocked.

While Russia has been ramping up restrictions on VPN and other circumvention technologies in recent years, our research indicates their censorship apparatus still lags far behind that of China and Iran. The country’s decentralized system of censorship currently means that many websites were accessible on some networks while being blocked on others.

We will continue to measure the blocking of VPN and other technologies in these countries and document any significant changes in their respective digital censorship systems.

Digital Repression & VPN Blocking:

The blocking of censorship circumvention and privacy-related websites strongly aligns with broader digital repression tactics. In fact, the average digital repression index score among the ten countries above is almost 10 times higher than the global average.

The index compiled by Steven Feldstein includes various factors such as government surveillance of social media, the dissemination of disinformation, internet shutdowns, and social media censorship.[1]

This data reveals shows that access to VPN and other privacy enhancing technologies is being curtailed in the very countries where they are needed most.

Which Websites are Blocked the Most?

Censorship is rarely a uniform process. Certain websites may be accessible for some while inaccessible for others. It can be determined by the part of the ISP’s network someone is accessing, where in the country they are, and the nature of the censorship apparatus they’re interacting with.

However, some websites were blocked more consistently than others across multiple countries. Among the countries that interfere with the internet the most, many well-known VPN apps and circumvention tools were almost completely inaccessible.

The Tor Project‘s website was the most consistently blocked website among the 10 countries that restrict access the most, followed by a variety of well-known VPN providers.

Not all censorship-evading tools were blocked, however. Ceno, a mobile browser designed to evade censorship; OpenPGP software; and Lokinet were all accessible in almost every country. These discrepancies highlight the global cat and mouse game between censors and their populations and suggests that several avenues around censorship and digital surveillance remain.

The following table shows a selection of the websites blocked among the 10 countries that restrict access to VPN and other privacy enhancing technologies most consistently. The figures refer to how frequently the website was rendered inaccessible in each country.

How are Websites Blocked?

Internet service providers use a wide variety of tactics to block websites following government directives. Our analysis shows that DNS tampering is the most common form of disruption in China and Iran.

The rest rely largely on HTTP/HTTPS interference. This broad category includes censorship enabled by deep packet inspection (DPI) technology and TLS interference.

Interestingly, IP-based blocking is now considerably less common than it once was. Largely, that’s because more advanced and targeted methods of censorship have now become readily available.

China’s use of DNS interference has been well-documented, with a recent report concluding that the Great Firewall’s “DNS censorship has a widespread negative impact on the global Internet, especially the domain name ecosystem.” The report also outlined how the affected DNS responses often served US-based IP addresses rather than the correct domain, and therefore directs unwanted traffic towards US-owned websites.

Chart showing the most censorship methods used among countries that block access to VPN websites most frequently

Censorship Methods Explained

- DNS Interference: disruption to a connection at this level can take many forms. A DNS resolver can be configured to provide the wrong response or the DNS query can be intercepted and tampered with via DPI technology. The easiest type of DNS interference to document occurs when a DNS resolution returns an IP address known to host a government block page.

- HTTP/HTTPS Disruptions: despite many people now using the encrypted HTTPS, censors are still able to monitor and block these connections. This can involve terminating the connection, dropping packets or RST reset injection. It’s even easier to block websites that are still using using the unencrypted HTTP via transparent proxies.

- TCP/IP Blocking: This relies on an ISP adding a specific IP address to a denylist. Any connections to the IP address will then be blocked by the censors. It’s a cheap and technically straightforward method of blocking content but it risks taking down multiple sites hosted on one IP address and therefore may have unintended consequences.

- Failure: This refers to instances where OONI was unable to automatically determine the cause of interference. While it may contain some false positives or indicate that an error occurred while someone was running the OONI probe app, recent research has shown the majority of tests flagged as failures do represent government blocking.

Each of the different types of interference relies on different technologies and procedures. However, all of them can be bypassed with the use of a reliable VPN. For specific figures on the censorship type used by each country please refer to the VPN blocking data sheet.

Methodology

To analyze the countries that block access to VPN and other censorship circumvention technology the most, we downloaded data from 1 Jan 2023 to May 15 via OONI. The data was cleaned to remove any incorrectly labelled domains and any countries with less than 5,000 measurements were discarded to ensure accuracy.

Failures were included in the report following a manual review of the measurements which indicated the vast majority had been incorrectly labelled and were instances of blocking, in line with recent research carried out by OONI. The overall percentage was generated from the average percentage across domains as some were tested more than others.

Footnotes

[1] https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/5dnfmtgbfs ↩